One of the things I do in my professional life is deal with contaminated sites.

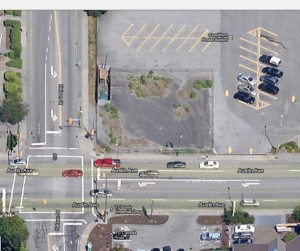

In the same way that whenever I tell anyone I am geologist they ask me about when the next earthquake is going to happen (short answer: I have no idea), when people find out I work with contamination, they always ask about old gas stations. Why are there all these old gas station lots with nothing on them but weeds and white pipes? Or more commonly: what is going on with the old gas station at the corner of XXX and YYY?

It is a long story, and regular readers know how much I love long stories.

In British Columbia, there are two pieces of related legislation – the Environmental Management Act and the Contaminated Sites Regulation – that control how contaminated land in the Province is managed. Municipalities have very limited powers over contaminated lands, unless of course they own the lands. It is the form of the EMA and CSR that cause these valuable urban commercial lots to sit empty for years.

A contaminated site becomes a capital-letter Contaminated Site when the owner of the property applies to the City for one of 5 specific permits named in Section 40 of the EMA: Subdivison, Rezoning, Development, Demolition or Soil Removal. The City is required by the EMA to collect certain information from the owner and send that off to the Ministry of Environment prior to issuing a permit. This makes sense, when you think about it. Those 5 permit types will change the character of the site – evidence of past property uses disappear when one of those 5 permits are issued. The Province wants to take that opportunity to document whether there is any contamination before evidence of that contamination disappears. If the site is contaminated, then the Ministry will most often prevent those permits from being issued until someone deals with the contamination.

So if you have a gas station, and you want to tear it down and put in condos or a In-and-Out Burger, you need to demonstrate to the Ministry that the land is not contaminated before you change the use. If it is contaminated, you need to either clean that contamination up or demonstrate through a rigorous science-based “Risk Assessment” that the contamination is contained, isn’t impacting your neighbours, and will not cause harm to human health or the environment at any time in the future. If the contamination is not stable, or if it could possibly cause harm, then you are not getting your permit, and your condo-building or burger-schlepping dreams will have to wait.

Cleaning it up can mean a lot of things. Sometimes, you just go in there with an excavator and dig out all of the contaminated soil and throw some ORC in the hole to cause hydrocarbon-eating bacteria to bloom in the groundwater. Bob’s yer uncle.

However, if the contamination is a long way down, it can be really expensive to dig it out, especially on an urban lot. Sometimes the contamination has migrated to include the neighbouring property, and the neighbour doesn’t want their building to be excavated. Disposing of this contaminated soil can be expensive. The cost of a complicated excavation can easily exceed the value of the land.

Alternately, in most cases the contamination will not last forever. Gasoline spilled in the ground will migrate downwards until it hits groundwater, then sit on top of the groundwater like Cointreau on top of a B-52. Some of it evaporates and moves back up through the soil, some is dissolved in the groundwater and flows away- diluting with distance. Some simply breaks down chemically in to less harmful compounds, while some gets eaten up by natural hydrocarbon-metabolizing bacteria. All of these degradation processes can be helped along from the surface.

You can stick wells in the ground and blow air down into the hydrocarbons and groundwater (“air sparging”). This breaks up the hydrocarbons so they dissipate, increases the evaporation, and provides fresh oxygen that encourages bacterial decomposition of the gas. You can also stick tubes higher in the ground and suck out the vapours, accelerating the dissipation. You can stick chemicals down the wells that will accelerate the degradation (but this is tightly controlled by the Water Act – you cannot stick the kind of dispersants they used in the Deepwater Horizon spill into a well in BC- things like Milk of Magnesia are typically used to boost oxygen levels).

Regardless, this type of in-situ remediation can take years or even decades, and in the meantime we can end up with a vacant lot, surrounded by a rental fence, with white pipes sticking out of the ground everywhere. Those white pipes are monitoring wells, which are used to keep track of the groundwater conditions, or the air sparging or vapour extraction wells for in-situremediation systems.

Or, of course, the owner can do absolutely nothing. (In reporting, this is what they call “burying the lead”). You see, nothing in the Environmental Management Act or the Contaminated Sites Regulation actually forces the owner of a contaminated site to clean it up.

That’s right. The owner is limited by what (s)he can do with the contaminated land (because they can’t get those municipal permits), but unless they have a compelling business reason to do something about the contamination, there is no law or other requirement saying they need to take any action towards cleaning it up. So the weed-covered empty lot can sit there literally forever.

It is at least theoretically possible for the Director of Waste Management (the senior bureaucrat in the Land Remediation Section of the Ministry) to order an owner to clean up contamination, but that power is very, very rarely exercised. In practice, the Ministry only does this if there is an imminent risk to persons or property caused by the contamination. Not unprecedented, but very unusual. There is no sign the Ministry is interested in increasing this power. And there is nothing a City or neighbouring properties can do to compel the Ministry to take this action.

So why is it (apparently) always abandoned gas stations? Near as I can tell, there are three reasons for this:

First, pretty much every gas station built before 1980 is a contamination nightmare. The old technology of buried single-walled steel tanks almost invariably leaked after a few years in the ground. Since gas was so damn cheap before the 1970’s oil crises, it was of little concern to most station owners if they lost a few gallons a day to leaks, presuming they even noticed. It was cheaper to let it happen than to dig the tanks up and replace them. A few gallons a day can, however, add up to a hell of a lot of hydrocarbon in the ground over several years. Then there was the waste oil and solvent disposal methods from the 60s. At a time when PCBs were used to clean carburettors, let’s just say housekeeping to protect the environment was not standard practice at Cooter’s Garage. This is no longer the case, I hasten to note. Modern gas stations use double-walled vacuum-sealed plastic underground tanks with automatic leak detection systems, and are very careful to recycle their valuable waste oils and solvents, mostly due to tougher laws. The legacy of old practices still haunts us.

A second factor is that there are far fewer gas stations today than there were 40 years ago. The smaller two-pump Mom’n’Pop operations have been replaced with larger multi-bay major company franchises. This means many of the former stations from the Century of the Car have been closed in the last couple of decades, and they all probably have contamination issues.

The third factor is that the closed stations usually belong to large multi-national oil companies. These companies have a lot of assets, and are in no big rush to divest themselves of fiddly little assets like a block of City land. The minuscule cost of paying property tax on an empty lot in New Westminster disappears when these companies are making multi-billion-dollar revenues. Commonly, the cost and hassle of cleaning up the land isn’t offset by the selling price they could get for it. They can sit on it for years, maybe the contamination will get better with gradual degradation and dissipation. Or not.

One thing they do not want to do is sell it without cleaning it up first, and that is, again, because the CSR does not allow for the “persons responsible” for the contamination to sell that liability. Nothing (except for your bank’s loan officer) prevents you from buying a contaminated site, but you cannot legally “buy the contamination”.

This actually makes sense. The last thing we want is for every owner of a contaminated site to sell that liability to some numbered company registered in Belize. That company could buy up 10 contaminated sites then go insolvent and disappear, abandoning the land for the Province to clean up. No-body wants that.

So the person who caused the contamination will always own it, as long as they exist. The big oil companies plan to exist for a long time. If they sell you their contaminated land, they no longer control what you do on that land. You could go back and clean the contamination up, and send the bill to the Oil Company, but if they wanted to spend that money themselves without you being the unaccountable middle-man. You could even conceivably do something that harms yourself or others with that contamination that belongs to the oil company, and the oil company will be responsible for some of that harm. Oil companies hate risk, so they would rather just own the land, put a fence around it, say “no trespassing” and do whatever due diligence is required to keep anyone from messing with their contamination. Just to be on the safe side.

So too often, the most rational business case is to just let that white pipe farm sit there, contributing nothing to the community for perpetuity. And there is nothing the City can do about it.

Some time in the next week or two, I will write Part 2 – about what the Province, Cities and neighbourhoods can do about these sites.

Fascinating piece. I’d often wondered why it seems like there’s so many empty lots where gas stations used to be around the GVRD.

Great article. I’ve always wondered about these sites. Some sitting right in the heart of downtown. Do you know about the site at Davie and Burrard? That one is covered by a community garden. A so much better use for the space than a weedy fenced lot. Although if the site is contaminated one does wonder about using it to grow vegetables.

Growing veggies on contaminated lots isn’t that hard. The dirt is kept in a box, and doesn’t come into contact with the asphalt underneath.

Sol Foods Farms (http://solefoodfarms.com/) does this in various places in Vancouver. To quote their website,

“We have developed a system of raised moveable planters that can be stacked on a truck with a forklift and moved. This both isolates the growing medium from contaminated urban soils, allows for production on pavement, and satisfies landowners who cannot make valuable urban land available on a long-term basis.”

Thanks Doug

Funny you should mention Burrard and Davie – that will feature in Part 2! (Maybe this weekend?)

There was another way to clean these up, and Bennett Environmental does it – burning the dirt, capturing any heavy metals, etc, out the other end.

It’s not just gas stations that leak hydrocarbons into the soil. Living in old heritage homes for the last 11 or so years, I’ve discovered the joys of old, buried oil tanks, and the cost to deal with contaminated soils. Fortunately, my education has all been second hand.

You mentioned that the # of gas stations has gone down, as a multi-bay behemoths fill in the landscape. There are also a lot more cars than there were 30 years ago. I think a lot of it has to do with fuel economy. A modern Honda Fit gets significantly better gas mileage than a 1970s Cougar XR7 (we had one growing up, and it was sweet), and I suspect that also might be why we don’t need fueling stations on every corner.

Anyway, great article, P@J.

Very interesting! thanks.

This comment has been removed by the author.

Thank you for this well researched and effectively written overview of a phenomena manifesting itself all over our country. The richest 1% of property owners contaminating a public space, privately held, with no intentions to remidate or make use of it. Have you discovered examples of expropriation where the government has confiscated the land back for public purposes, relieving the title holders of the ability to make use of the space? I would love to see a precedent of “use it or lose it” in our current system of governance. Maybe another idea would be to not ALLOW Environmental Terrorists to clean up their own mess. DWH: BP used dispersants illegal in Canada.. In one of the biggest bodies of water serving a majority of all life in the western hemisphere. Did they employ best practices to mitigate environmental impact or the cheapest dirtiest option to get it out of the public eye.. For now. Haven’t seen much shrimp in the grocery stores lately.

Great article you answered all my questions. Where can I find part 2?

There is a property at Austin and Nelson in Coquitlam that is about to be developed by Beede I wonder if it will be checked to see if its contaminated it hasn’t been a gas station for 15 or so years

Without knowing the specifics of that project, I would say two things: No Developer is going to take the financial risk of buying a former gas station site without the contamination being remediated to the satisfaction of the Ministry; Any redevelopment of a site like this triggers a bunch of permits (Rezoning, Development Permit, etc.) listed in Section 40 of the Contaminated Sites Regulation, and those permits cannot be issued unless the Ministry is satisfied the site has been remediated. The CSR isn’t perfect, but it is a really good at catching redevelopment sites and assuring that Human Health and the Environment are protected through that process.