The top of the Grand Canyon, and much of the rubbly plain surrounding it, are made up of rocks of the Kaibab Formation. The Kaibab is a limestone unit, somewhere around 270 million years old, which puts it in the middle of the Permian Period of the Paleozoic Era.

The world was a different place in the Permian. This is a time before there were birds or mammals, even the dinosaurs had yet to develop. The dominant land animals were synapsids, which look rather like modern lizards but were more mammal-like than reptilian (with differentiated teeth and quite possibly fur). They were almost completely wiped out in the Great Permian Extinction (lucky for you they weren’t, as one of your ancestors was a Permian synapsid).

There were no flowering plants in the Permian, but cycads, ginkgoes, and ferns were common. In the sea, 300 million years of Trilobite domination was about to come to an end, and echinoderms and mollusks were rising, especially a new-fangled cephalopod mollusk, the Ammonite, which was starting it’s impressive 200 million-year reign as king of the Sea.

The Permian was also the last time that all major continental land masses were collected together through Plate Tectonics into one “supercontinent”- Pangaea, leading to bad T-shirt ideas ever since (people calling for Pangaea’s reunion rarely consider that the supercontinents correlate very well with massive declines in biodiversity, but I digress). In the part of Pangaea that is now northern Arizona, there was a shallow sea facing to the west, with the shoreline shifting around somewhat, as they are apt to do on million-year time spans, which brings us to the limestone.

Limestone is generally deposited in shallow ocean water as a result of biological precipitation of carbon dioxide and calcium out of the water column – which is a fancy way of saying: it is all shells. Not just shells of bivalves like clams and oysters, but structural parts of corals, echinoderms, sponges, and perhaps most importantly, microscopic plankton. As this pile of dead and discarded shell material is compressed, heated and dewatered, it cements together into a very hard rock: limestone. Well, it is actually kind of soft by rock standards, and it is easily dissolved (on a geologic timescale) when exposed to meteoric water. However, it often forms large, homogeneous blocks that can be very resistant to erosion in arid place, like the Colorado Plateau into which the Grand Canyon has incised.

In places west of the Grand Canyon, younger rocks are piled on top of the Kaibab, but around the canyon, these younger rocks have been eroded away at some point in between the 270 Million years since it’s deposition in the shallow ocean and it’s current exposure more than two Kilometres above sea level.

|

| Did I mention my |

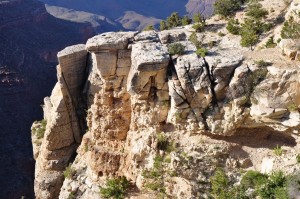

The Kaibab is hard enough to form vertical walls at the Canyon rim, some more than 300 feet high. It is also distinctly grey in colour, making a visible band around the canyon rim, and is easy to differentiate from the reddish sandstones and shales below. The underlying Toroweap formation is not as resistant, and forms rubbly slopes below the Kaibab cliffs.

|

| Kaibab – you can recognize it from 10 miles away. |

Close up, the Kaibab is grey in colour, and is variously massive (showing little internal structure) or mottled with chert nodules and fossils. It is also variously mixed with relatively thin shale or sandstones beds, just enough to give a sense of bedding.

|

| This poor, suffering bastard could use a bed. Fortunately, there is beautifully expressed bedding in the Kaibab Limestone outcrops behind him! |

|

| Chert nodules weathering out of Kaibab limestone. Note pointing doofus for scale. |

“Chert” is a micro-crystalline form of quartz (more or less pure silica) that is much harder and less soluble than the limestone so it really stands out from the limestone surface. These nodules formed in the limestone when it was buried and hot groundwater with silica dissolved in it percolated through the limestone depositing crystals. These look like fossils, and indeed some of them do form around incongruities in the limestone caused by fossil structures, or in tunnels bored through the sediments on the ocean floor by various animals who might be grazing through the sediment looking for food (like worms do in soil) or making tunnels or tubes to live in (like some types of shrimp or clams might do). These are “trace fossils”, and I will go on at length about them in later posts.

I like trace fossils.