Wes asks—

I’ve heard a lot recently about road pricing, as a means to fund transit and road infrastructure. What does this actually look like ? Ts it transponders and sensors all over the Metro area? Is it simply a declaration at time of insurance renewal of Vehicle KM last year and current Vehicle KM ?

I think the short answer to this question is we don’t really know yet, but we can make a pretty qualified guess.

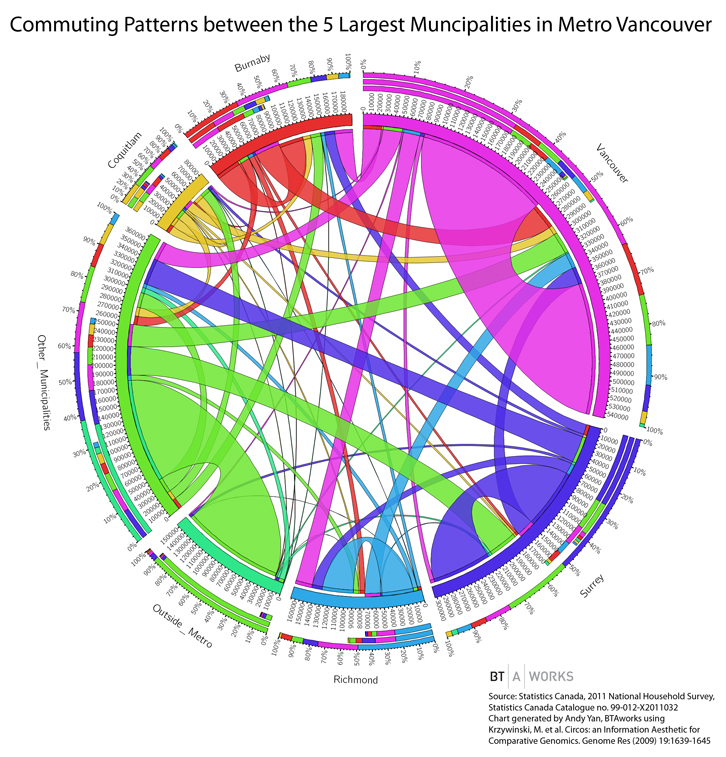

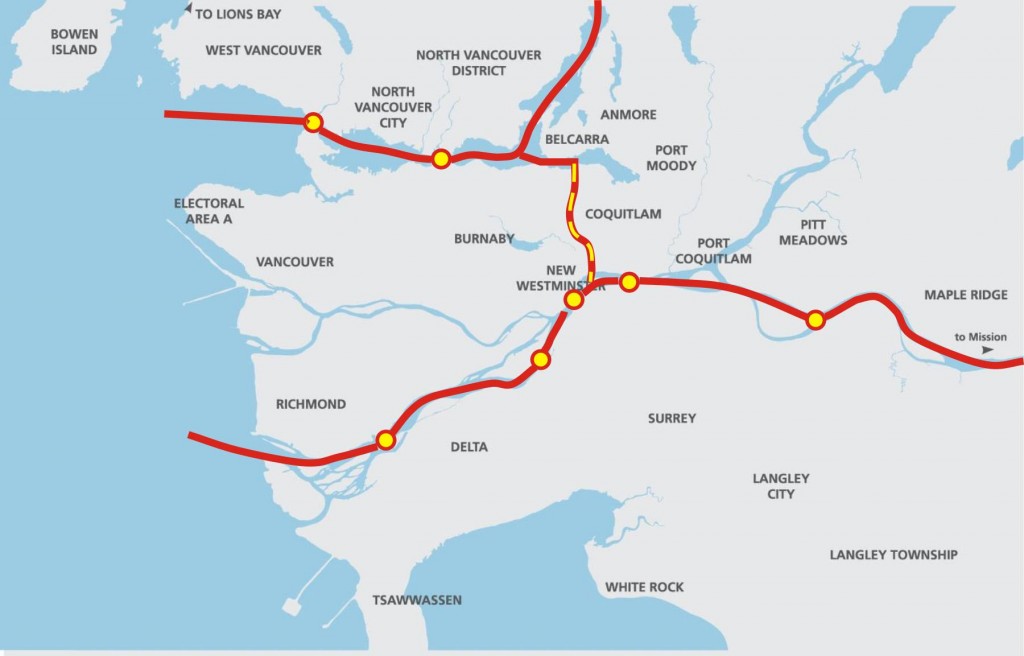

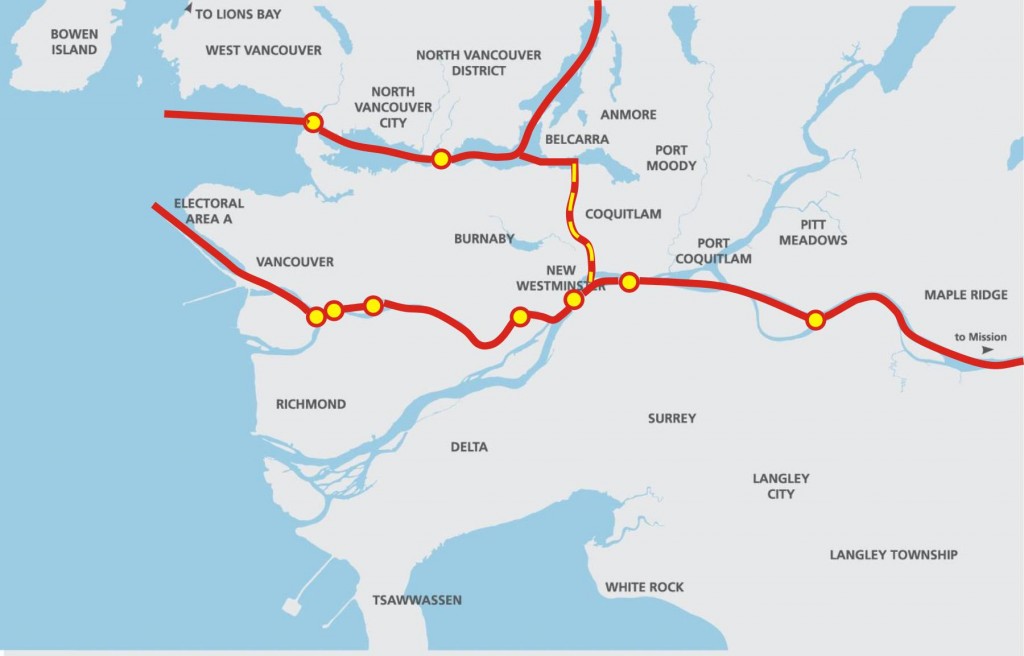

In my earlier posts, I talked about how the “$1-toll-for-all-bridges” idea could be refined into a more practical regional road pricing model. This model would expand the Port Mann / Golden Ears transponder and licence plate scanning model to maybe a dozen locations at logical “pinch points”. That is a quick and dirty way to make it work, and uses proven technology and bureaucracy that already exists. I don’t think anyone thinks this is the long-term solution, but it is a move we can get going very quickly and get the public used to the unpopular idea that roads aren’t free, if we have the political will to make it happen.

The long-term plan is something that is discussed in the Mayor’s Plan, but was blithely ignored by the media and Bateman during the Plebiscite. The plan was very clear that the sales tax was a 10-year cash infusion for capital improvement to build the required alternatives prior to the implementation of a proper road pricing model. The plan was for increased user revenue and road pricing to increasingly fill the revenue gap to allow for continued development of the system:

“LONGER TERM: Staged introduction of mobility pricing on the road network Over the longer term, the Mayors’ Council is committed to implementing time-and-distance based mobility pricing on the road network as an efficient, fair and sustainable method of helping to pay for the transportation system.

“Mobility pricing on the road network would help generate funding to implement the remainder of this Vision and shift taxation away from the fuel sales tax—which is a declining revenue source due to increased vehicle efficiency and leakage to areas outside of the region. By generating $250 million per year from a fair, region-wide approach to mobility pricing on the road network, we will be able to fund the remainder of this Vision and at the same time reduce the price paid at the pump by about $0.06 per litre.” – pg. 36, Regional Transportation Investments: a Vision for Metro Vancouver

Systems to make this work are limited to a few existing (and a few speculated) models. The model common in the US, Europe, and Australia of charging distance tolls on limited access freeways (“Turnpikes”) based on how many exits you have passed, is probably not a practical system for BC. We have few true limited-access roads: Highway 1, and 91 and 99 south of the Fraser. Even the new South Fraser Perimeter Road is doesn’t really fit the limited access model for much of its distance. With interconnected surface roads providing alternatives and a demonstrated proclivity for local drivers to value their money more than their time, this approach is doomed to a CLEM7 failure from the start.

There are two other ways to imagine road pricing, both potentially administered by ICBC.

The simplest is a charge-per-use model where every year you report your mileage to ICBC when you update your insurance, and pay a per-kilometer charge. This is potentially the least intrusive model, but the model most likely to see tax avoidance. With modern cars, it is a bit of a complicated process to just “crack open the odometer and roll it back by hand”, a la Ferris Bueller, and there is generally electronic data storage onboard that may have be useful. Of course, this would be easier if we still had an AirCare infrastructure to put to use, but it might be in inferred “unfairness” of the model that makes it least palatable. Expect questions like “If I take a road trip to San Francisco, why should I pay BC roadtax on that?” or EV owners whinging that they should get exempted, as they often conflate their reduced GHG output with other urban design issues related to the single occupant vehicle. This also does not allow differentiation of rates based on where and at what time the mileage is run up, significantly reducing the Transportation Demand Management (TDM) utility. Should you pay as much for a Sunday drive to the park as you do for crossing the Pettullo at rush hour?

The model that would likely work best is, unfortunately, the one that is going to create the most political pushback for mostly nonsensical (and therefore hard to refute) reasons. This is the placement of GPS-type transducers in all vehicles insured in BC, and piggyback on the existing cellular networks to track all vehicle movement. This is a significant data-crunching challenge, as there are something like 2 Million vehicles registered in the Lower Mainland, but the benefits are huge. True distance and time-of-day charging can be done to get the best TDM benefits. It would be arguably the most “fair” process to balance the needs of all users, although there would be a Smart-meter type push back.

There would also be significant devil-in-the-details around how the pricing scheme was developed. In todays’ provincial and regional political climate, it would be hard to wrest that decision making from the politicians, and parochial battles would no doubt ensue. There could be interesting side benefits (it would essentially end car theft, as stolen vehicles could be easily and quickly be tracked) but these would no doubt be offset by the brain melt it would cause for civil libertarians (why does Big Brother need to know where my car goes!?). Ultimately, this is probably politically impossible in our current regime. Perhaps this situation will change as the next generation raised on smart technology are the descision-makers, and we are ready to re-think transportation as a technology challenge.

This speaks somewhat to Helsinki’s one-card model for all transportation modes. They are building a scheme where you pay for a “transportation card”, and you can use that to pay for all transportation choices: road tolls, train tickets, bus passes, bike share, taxis, Car-2-Go type car share, everything. Prices can be made flexible for time/congestion/availability issues to manage the entire system more efficiently, and you can walk out the door of a building and decide what mode (or combination of modes) is best to get you to your next destination with seamless transitions. But we are nowhere near there yet in North America.

In the end, the tolling of bridges (and possible other “gateways” such as North Road, 264th Street, Horseshoe Bay, the US Border, etc.) through an expanded transponder/licence plate scanner is the best we can practically hope for in the decade ahead. It has been working in Singapore for years, and has seen success in London and other European cities. It is a little kludgey, and definitely sub-optimal, but as I have said before, we can’t let the perfect be the enemy of the good, and we need to start moving this conversation forward as a region.