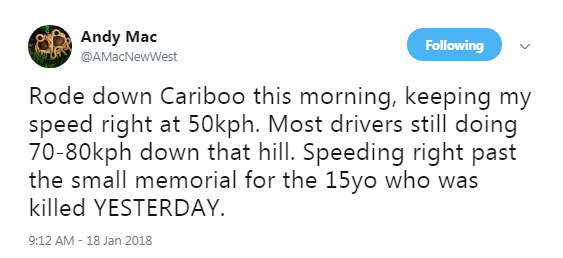

Over a period of four days, two pedestrians and a cyclist were struck by drivers of vehicles on the same section of Cariboo Road. The first pedestrian, a 15 year old, died at the scene. It’s heartbreaking.

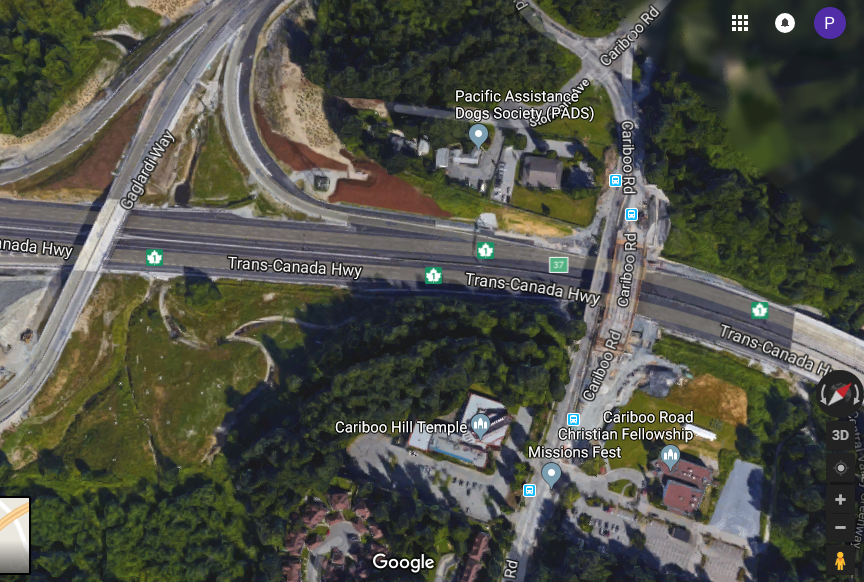

This is a piece of road I am familiar with. It used to be on my daily commute when I worked in Burnaby, and is still part of my regular cycling routine. So am quick to add my “anecdata” along with the list of people commenting that the crosswalk in question is a terrible design. It is a crosswalk that provides access to a well-used bus stop across the street from a residential area, but it is around a corner at the base of a big hill where the speed limit is ostensibly 50km/h, but every piece of the road’s design (separated centre, wide shoulder, 5m lane widths, sidewalk buffer) tells the driver to go much faster. And drivers do go much faster.

So there will be wringing of hands, and pressure for the City to fix this situation. Likely, some sort of pedestrian-activated light will be installed at the cost of a couple of hundred thousand dollars that will marginally increase pedestrian safety, but will add one more step a pedestrian must take (hit a button, wait for a light cycle) to beg for the right to safety while moving through public space. Meanwhile, a little bit of targeted enforcement by the police will increase the perception of something being done until their attention is drawn elsewhere and driver’s behaviors revert to what the road design is telling them to do. The 85th percentile will again sneak up to its design point.

I would be hopeful for, but not expecting, a more sustainable long-term solution, one that would meaningfully increase safety for all users. Reduce the lane width to something like 3.5m (which would provide opportunity for a separated protected cycling path on this well-used route). Complement the pedestrian light with a raised crosswalk, paint and texture treatment to send appropriate speed signals to the drivers. Increase the number of protected crosswalks along Cariboo Hill so people can access the Cariboo Heights residential Co-op and Briar Road, and to again signal drivers that this is a residential area where they should be driving 50km/h and expect pedestrians, not an 80km/h freeway on-ramp. This would, of course, be expensive, but the Google Earth air photo still shows the millions of dollars recently spent here to allow drivers on Cariboo Road to drive faster through here as part of a regional motordom expansion project…

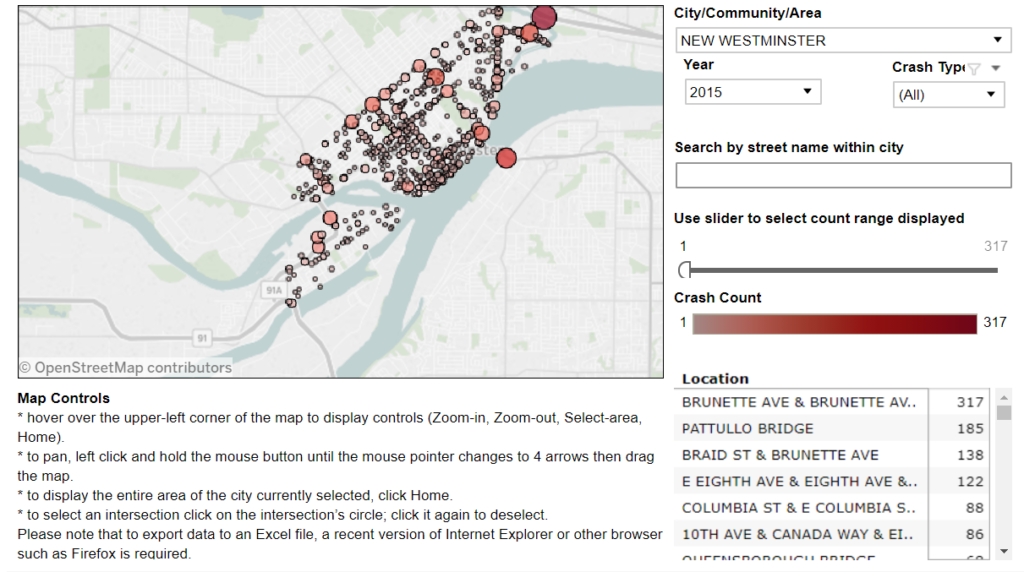

Uncharacteristically, I am not going to hate on Burnaby here. That would be too easy and unfair. This situation is not unique to Cariboo Road, and it is not unique to Burnaby. It in no way undermines the seriousness of this situation to say these three incidents in such close proximity are an unfortunate coincidence. Realistically, I can name a dozen other areas where similarly hazardous conditions exist, and municipalities like Burnaby, Richmond, and (yes) New Westminster are slow to react to them.

That these safety issues are so common is part of the reason we are so slow to react; there’s a lot of infrastructure to fix and a limited infrastructure improvement budget. Still, too much of it is spent on “getting traffic moving” in places like this, were public safety would suggest the opposite. I could go off on a long tangent about “warrant analysis” here, but instead I’ll just reiterate that even if the best intentions exist, priorities need to be set. There simply isn’t enough money to make every pedestrian crossing as safe as we would like, because there are too many unsafe intersections and crossings. 70-odd pedestrians are killed every year in BC, the vast majority at a marked crossing or intersection, demonstrating that we have a lot of work to do when it comes it engineering the protection of pedestrians.

However, engineering can only get us closer to the safety we desire (and please spare me the long digression into autonomous vehicles, the fantastical promises of which seem to commonly fail when pressed against some simple inquiries into their remaining challenges). I’ve recently-enough ranted about how the vehicles pedestrians are forced to share space with are increasingly dangerous to those pedestrians, but haven’t really called out another trend supported mostly by personal anecdote: an increasingly callous disregard for the safety of other demonstrated by people driving cars in British Columbia, and the apparent reluctance of Police and Crown Counsel to meaningfully address this public health emergency.

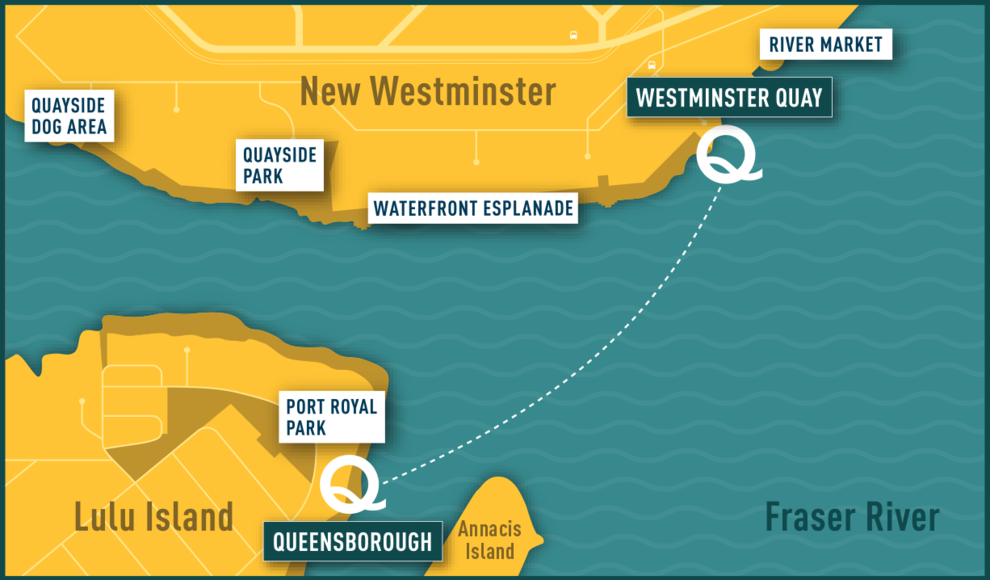

We have work to do as municipalities (working with and supported by TransLink and the Ministry of Transportation, I hope), and I am proud that New Westminster’s draft 2018 capital budget is showing a serious commitment to meeting the goals set out in our Master Transportation Plan – we are now spending as much on pedestrian and cycling improvements as we do on road repair and asphalt to “keep traffic flowing”. But at some point, we are going to need to convince drivers to meet us half way. We need to change people’s minds about their cars, their entitlement, and how that threatens the safety of our communities.

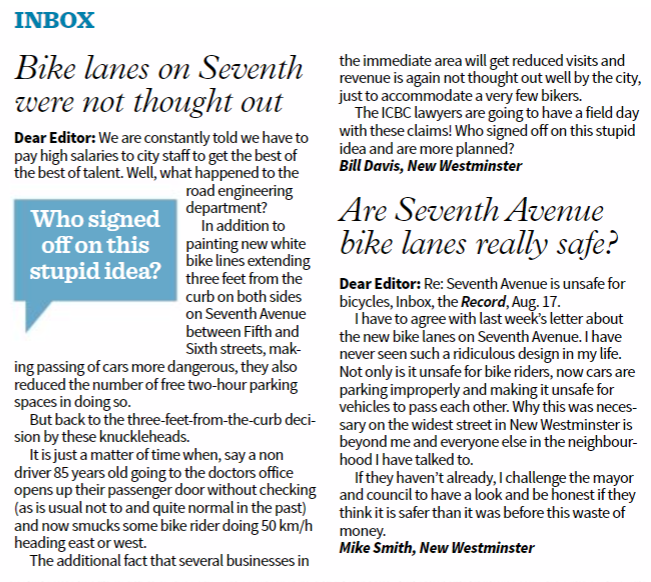

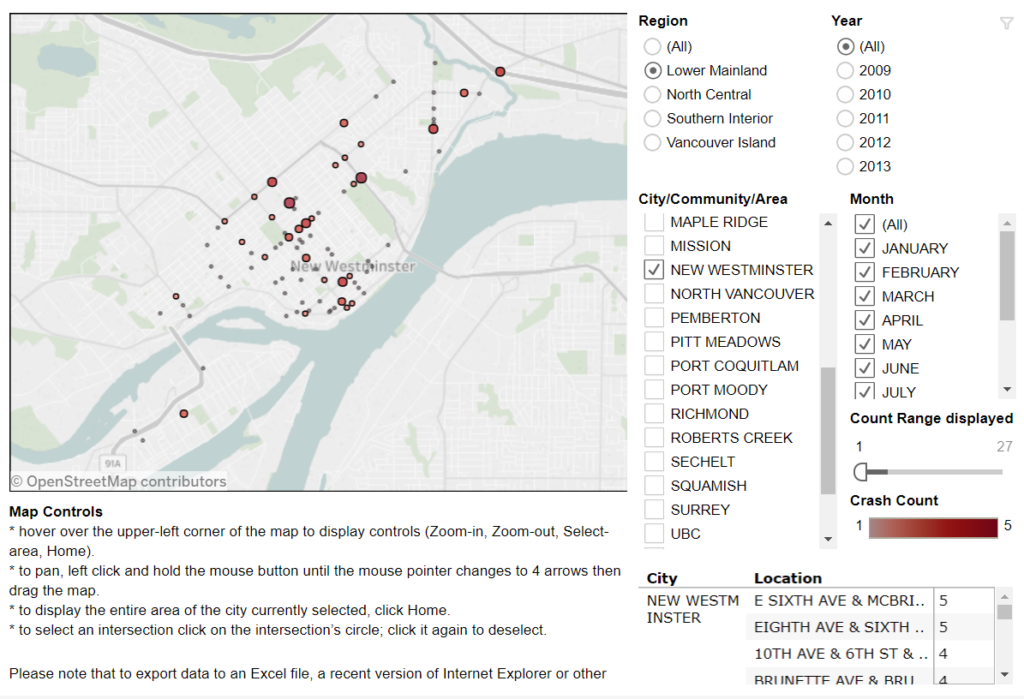

The Crosstown Greenway improvements are very small part of our transportation budget (less than 3% of this year’s budget for road improvements), and has numerous potential benefits to the community at large. As the City’s first foray into modern separated bikeway design, it may have a few kinks to work out, and it may take a bit of time for drivers to get their head around the new layout, but it is based on

The Crosstown Greenway improvements are very small part of our transportation budget (less than 3% of this year’s budget for road improvements), and has numerous potential benefits to the community at large. As the City’s first foray into modern separated bikeway design, it may have a few kinks to work out, and it may take a bit of time for drivers to get their head around the new layout, but it is based on