Last month I put forward a motion (passed unanimously by Council) asking that we commit to planning and building a AAA Active Transportation Network in New West. I thought I would take a bit of time to outline what that means (from my point of view, anyway, because I am always cautious not to speak on behalf of all of Council) and talk about why I think it is important for us to do it now.

As I am often using terms more familiar to transportation advocates than your average person, maybe I could start by talking about the italicized-in-blue term I just used. Because this is not just about bike lanes. Though it may include bike lanes.

“AAA” stands for All Ages and Abilities, to differentiate it from infrastructure built specifically for me – the “avid cyclist” stereotype. I’m a healthy middle-class middle-aged sorta-fit guy who has been riding bikes pretty consistently for more than 45 years. I have raced bicycles (mostly mountain bikes; remarkably unsuccessfully), I have commuted by bicycle in big cities and small towns, ridden next to highway traffic over mountain passes sometimes more than 100km in a day. I even spent some time as a bicycle courier in downtown Vancouver, back when that was something people did. Because of this history, I have a high tolerance for danger and an inflated sense of invincibility. I don’t need bicycle lanes or special infrastructure to get me riding my bike. I’ll ride anyway (and probably irritate a few drivers on the way, but we’ll get back to that). AAA bike infrastructure isn’t for me.

Transportation advocacy used to be about people like me – wanting to make trips safer for a American Wheelmen (yes, that was the name of an early cycling advocacy group, and by early, I mean until the 1990s). But there has been a shift in North America since then, following after a couple of decades of progress in Western Europe, to shift towards making cycling infrastructure work for more people. Ideally, everyone who chooses or might choose to ride a bike (or trike, or quadcycle, or handcycle, etc.), but may not be avid about it. Like the way many people drive cars or ride buses, but aren’t avid drivers or avid passengers.

There is also advocacy around “880 Cities”, the idea that if you build a City that is safe enough to make an 8 year old and/or an 80 year old comfortable and independent in public spaces, it is making the space safe and accessible for everyone. You can read into that that people should be able to ride their bikes to school, even in elementary school (like I did as an 8-year-old). An 80-year-old should be able to ride as safely as they can walk, to expand their reach and options in a community and make them less reliant on cars (like my Mom does, with the help of her E-bike). To build for these users, we need to build AAA.

This corresponds with talking about Active Transportation Routes instead of the more restrictive “bike lane”. This means infrastructure should accommodate adult trikes or recumbents for people who may rely on the extra stability they offer. It should also be comfortable to share with people who rely on scooters, electric wheelchairs, or similar lightweight controlled-speed rolling devices. Multi Use Paths (MUPs), where pedestrians are mixed with rolling users should be built in a way that accommodates both user groups and their distinctive needs. Moving bicycles off of busy roads and onto sidewalk-style MUPs makes the bicycle riders feel safer from the larger, faster vehicles, but it may do so by making bicycles the larger, faster vehicles making some pedestrians feel less safe, unless a MUP is built what that in mind.

Finally, we need a network. Bike lanes are like roads, sidewalks, and pipes: they don’t do as much good until they are connected to something. Some people note they don’t see a lot of people using the Agnes Street bike lanes, or the bike lanes in front of the new high school, but both of them represent an important first piece of infrastructure that isn’t yet connected to a network. For users like me, it’s great to have those sections of increased safety; for less confident users, 100m of missing safety between two great bike lanes can be the barrier stopping them from riding on either. This is the issue being addressed by current region-wide “Ungap the Map” campaigns.

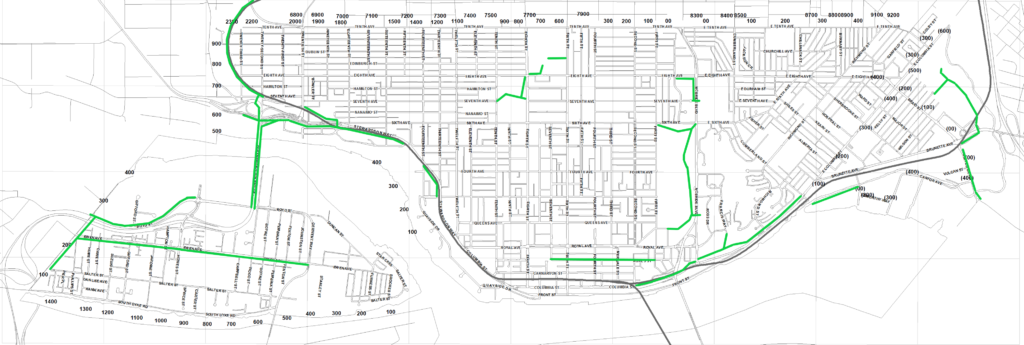

So, where is New West now? We are six years into the current Master Transportation Plan, and have made serious progress in pedestrian safety and accessibility. Though it lags behind a bit, we are starting to see some key parts of our planned cycling network come into place. However, the planned bike network envisioned in the MTP is no longer, I would argue, the vision for a AAA Active Transportation Network we would choose to develop if we were starting today. We can, and should, do better.

By way of sketching on the back of an envelope, our current network of infrastructure that meets AAA standards looks something like this: This is a map I sketched up using MSPaint just for discussion purposes. This is NOT an official City of New Westminster map, and possibly not even accurate.

This is a map I sketched up using MSPaint just for discussion purposes. This is NOT an official City of New Westminster map, and possibly not even accurate.

There is some good stuff there, but it is disconnected and incomplete. Of the AAA we have, it leans heavily on the MUP-in-the-Park bikes-are-for-recreation model of the 1990s.

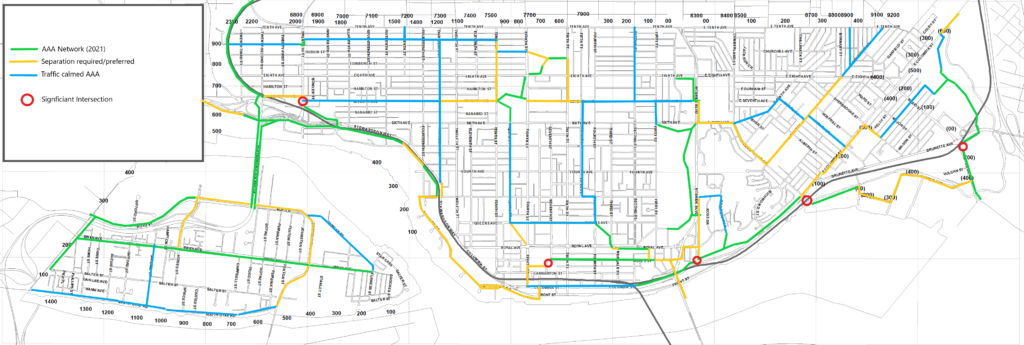

In my mind, a complete AAA network built off of our existing system would look something like this:

Once again, not a map created or endorsed by the City of New Westminster or anyone else. I just sketched this up to facilitate a discussion. Actual plans will probably look different than this.

Once again, not a map created or endorsed by the City of New Westminster or anyone else. I just sketched this up to facilitate a discussion. Actual plans will probably look different than this.

Note that there are two kinds of future AAA Active Transportation routes shown in my sketch. Those shown in Yellow would comprise separated and protected bike lanes and/or MUPs (like the Agnes Greenway or the CVG past Victoria Hill), where people rolling or riding are not expected to share space with cars. The other type is shown in blue, where bikes might continue to share road space with cars but only if there are specific structures to significantly calm the traffic and force cars on that route to move at bicycle speed. No cars passing bikes, no person on a bike placed between a moving car and a parked car, and intersections designed to be safe by people using all modes. There are several routes like this in Vancouver (I think sections of the Ontario Street or 10th Ave bikeways in Mount Pleasant qualify), and maybe London Street through the West End is the closest example in New West (though there could be some improved calming and signage there). There is some work for us to do to establish the standards we want to apply to safety/comfort of these routes to call them AAA, including the level of traffic calming we can achieve vs. the need to separate.

Finally, I want to emphasize that the time is now to do this work, for a variety of reasons.

One result of the pandemic is that it resulted in a generational shift in how people around North America move about their cities. Bicycle take up has happened at an unprecedented rate, such that stores across North America ran out of bikes and parts to maintain them. Add to this the battery and technology revolutions that have brought reliable e-assist bikes and other personal mobility devices that open up active transportation to many people who did not see that as a viable option previously.

Some communities have seen more rapid pick-up in this shift than others. And surprisingly (unless you have ever been the Madison Wisconsin or Boulder, Colorado), it is not warmer climate or flatter topography that correlates with this take-up, it is the availability of safe infrastructure. Like roads – build it and they will come.

Examples abound, but I’ll limit myself to two: In Paris, Mayor Hidalgo introduced Plan Velo, and committed to 1,000km of cycle paths, a key part of the 15-minute City vision, transforming her city into one that is now seeing close to a million bike trips a day. Recently, emboldened by a landslide re-election, she doubled down with another $300M investment in expanding bike lanes. The City of Lights is becoming a City of bikes.

Closer to home, the work Victoria has done since adopting a 5-year plan for a AAA bike network in 2016 has been equally transformative. With most of the network now installed, it is seeing incredible take-up, and Victoria has established itself in a few short years as one of the most bike-friendly cities in Canada.

At the same time, senior governments in Victoria and Ottawa are funding Active Transportation projects as never before, so we don’t have to pay for this alone. But right here in New West, we have introduced an ambitious climate action plan, framed around 7 Bold Steps. These goals will not be achieved unless we start shifting how we move around, and how we allocate road space in the City, and only a complete AAA Active Transportation network will get us there. The time is now to commit to this work, and to ask staff to give us the data we need to integrate that commitment in to our 5 year capital plans.