A second report to Council that came down last week was an outline on the Master Transportation Plan process. I have railed on about this in the past, and have spent much of the summer letting people know about the MTP during NWEP booth events. All along, we have been telling people it is coming, asking them questions about their transportation issues, and suggesting they get involved in the consultation process if they care about the future of the City.

The report to council outlines how the Master Transportation Plan will come about, and now that we have some details. It seems the first opportunity for public consultation will be during Stage2, and we can expect a lot of initial “community visioning” events like took place during the UBE process.

However, I want to talk about Stage 3, and about transportation models. First, the caveat part: I am not Transportation Engineer, so my opinion here is worth exactly what you paid for it. My expertise is in other areas, so I will be the first to stand corrected by those with more expertise or different facts. That said, during the UBE controversy, in discussions around the NWEP’s transportation forum last year, and by following along in transportation discussions with people like Stephen Rees, Voony, and Eric Doherty (who have a much higher level of expertise than I), I have learned a bit about Transportation Models, their strengths and weaknesses.

My concern about Transportation Models is that they generally fail to accommodate things like induced demand and the traffic demand elasticity – things that are vitally important for planning a transportation system in a built-out city like New Westminster, where the economic and social costs of building expanded road infrastructure are massive.

The basic transportation forecasting model works like this: You draw out a virtual transportation network to match your existing one. You then enter landuse parameters within and outside your study area, which tell you a bit about what is generating the trips (i.e, 30,000 residents here, industrial area there, commercial district over here, etc.). These create a model framework. Then you count your actual traffic, and calibrate your model so the traffic load generated in your model matches the traffic you measure in the real world. Then you take the Regional Growth Strategy off the shelf and apply the projected growth to your model: 10% more residents here, 15% more businesses there, etc. and count what that does to the traffic. If there are trouble spots that pop up, you mess around with your transportation network to make it work as efficiently as possible.

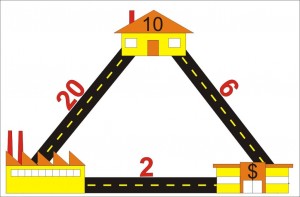

To demonstrate this, I can draw a ridiculously simple model. Let’s say you have a village with 10 houses, one factory and one shopping centre, and they are connected in a triangle (see below). We measure 20 trips between the factory and the house every day, and 6 between the houses and shopping centre, and 2 between the shopping centre and the factory. That is our model set up.

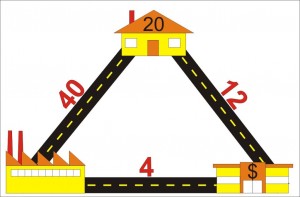

Now let’s say the Growth Strategy indicates we will double population in 10 years. In this case we double the number of houses (and for the sake of model simplicity, keep the factory and shopping centers in the same place, just assume they both double in size). We enter that in our model and presto: we get a doubling of all trips.

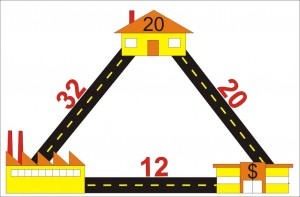

But what if the road between the factory and the houses can only handle 30 trips until it becomes hopelessly congested? In that case, the citizens have two options: sit in the congestion and accept their fate, or go around the “long way” which might take less time if the congestion gets bad enough. Some will choose to go-around until the time is equal on both routes, and the model might look something like this:

Since citizens hate congestion, they lobby City Hall to fix the problem. City Hall has two options to fix the problem: it can expand the road to accommodate the traffic, so things look like our second drawing up there. Or it can build another route to relieve congestion. (Now we enter into the world of the Braess Paradox, but let’s not go down that rabbit hole just now).

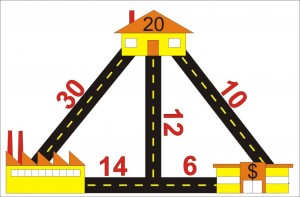

We can do all sorts of messing around with the road configuration to best accommodate the traffic generated by the growth, and this is how we can apply the model to make the most logical choices about how we invest our transportation money. However, (and this is the nut of the matter) it is assumed in these models that traffic (=trips) will grow to match the population increase. Whether you build a road to accommodate it or not is irrelevant to the model.

Let’s say you don’t do anything to expand road capacity. Do we really get 32 trips on the one road and 20 on the other? If 32 trips cause congestion enough to shift people’s behaviour and make them change road choices, perhaps it also induces some to not drive. Carpooling, transit, bicycling, or telecommuting become better options. Maybe building a bus route instead of building a road is better investment – we can move more people with less money (if a bus is cheaper than two more lanes).

With 8 of the trips from home to factory going via the Shopping Centre, won’t this cause people to shop in the way home, and reduce the number of specific trips between the houses and shopping centre? If we don’t build more road capacity to accommodate growth, will the number of trips actually be reduced?

One thing we noticed in the UBE process is that models are really good at predicting increased levels of congestion, but do not accommodate the idea that congestion has an upper limit before people stop fighting it, and find alternatives.

The result? People discussing the NFPR say that traffic on Front Street is at a dead stop, is constantly congested, is completely at a breaking point, then produce models that suggest the problem will only get worse until we fix it. Of course, if the roads are already at capacity, the problem cannot get worse, unless we add lanes in an attempt to fix it.

Transit is a real alternative when it is faster and more efficient that driving (Canada Line anyone?), cycling is an alternative if the distance is short enough, the trip is on safe infrastructure, an there are end of trip facilities available. Moving closer to your work, or working closer to home, is an alternative, when land-use planning makes this possible. Shopping locally is an alternative to driving across town to your favourite Megamart. Moving containers by rail and barge is an alternative. And yes, building more roads an option, but is it the best use of our resources?

Back the Master Transportation Plan, and I’ll be uncharacteristically brief here. Because the vast majority of traffic in New Westminster is through-traffic (something like 400,000 vehicles a day in a City with a population of less than 70,000) most of the factors that control traffic in our City – like landuse planning, growth in the rest of Metro Vancouver, the building of mega-freeways – are beyond our control. Therefore, it is possible that the only control we have is how we allocate our road space. In a sense, the only way we can control out own traffic fate is to manage the implied demand part of the equation. Will the model be the tool to do this?