This Post is actually an extended response to the comment by Ken, a Quayside resident and community builder, to my previous post about the Q2Q bridge. I thought his comments raised enough issues that I couldn’t do it justice just replying in a comment field!

Thanks Ken,

I will try to address your questions, but recognize that much of what you talk about occurred before my time on Council (so I was not involved in the discussions) and I respect that you have a much more intimate knowledge of the conversation on the Quayside over the last decade than I do.

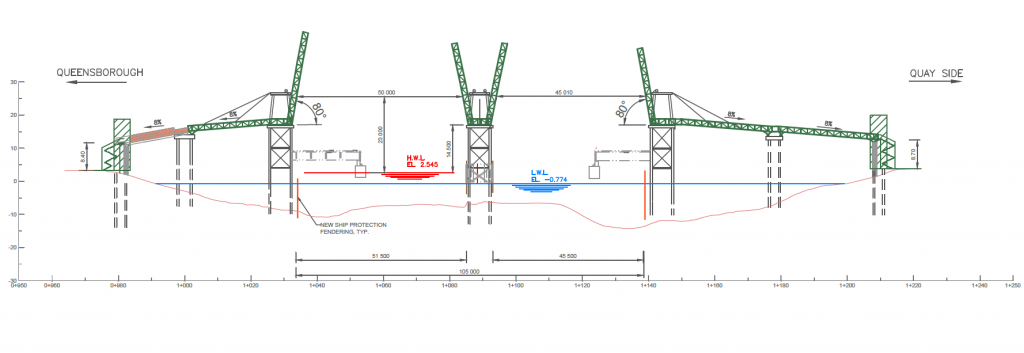

The project has indeed gone through various iterations in its history, and the initial plans ( here is a link to a report from the time) were to reach 22m of clearance to develop a fixed link that would get adequate clearance that we would not need Navigable Waters permission (read- not specifically need Marine Carriers permission) which required essentially the same height as the Queensborough Bridge. Conceptual drawings were developed based on the site conditions and some baseline engineering, and very preliminary cost estimates prepared. That concept was indeed reviewed by the Port (at that time, the Vancouver Fraser Port Authority) and note they even at the time preferred an upstream (east of the train bridge) location (see page 12 of that report I just linked to). Note also: that report suggests elevators at each end to improve accessibility. This is the concept that first went to public consultation, and concerns were heard about the need for long ramps that would have nonetheless been very steep, the overall height, the fate of the Submarine Park, etc.

The only alternative to all of that height was a swing/bascule bridge. To explore this option, the City asked some engineers to sketch and (very preliminarily) price some alternative concepts, including a bascule and a sidewalk attached to the rail bridge. The City again took these preliminary concepts to public consultation, and the bascule design clearly came up as the preferred approach, even recognizing it was potentially more expensive.

Now that a preferred concept was (hopefully) found, and the Q2Q crossing once again received endorsement from the new Council, it was time to actually pay a little more money to engineers to further develop the preferred concept to a level of detail that would allow screening for Port review. Not enough development for a full review, mind you (that will likely take several hundred thousand more dollars in engineering and environmental consultant fees and will no doubt also result in adjustments of the concept), but enough that it is worth the Port’s time to look at our concept and provide a detailed regulatory screening and provide us a pathway to approval.

That is pretty much where we are right now, and for the third time, this concept is coming to the public for review. The only thing I can guarantee you at this point is that if (and it is still an “if”, despite general Council and public support) this project is completed, it will not look exactly like the drawings you see on the page today. There is much engineering to do, environmental review to perform, and more public discussion to be had. Satisfying the Port’s environmental review will be months once we get to that point, and we can guarantee it will require some design adjustments.

There are also other adjustments I think we need to see based on public feedback this time around. Although I have held my cards close to my chest because I don’t want to prejudice the public consultation, I will admit up front that there are two things in particular I cannot tolerate in the plans as presented at the open house: the 8% ramps simply do not meet modern standards of accessibility; and the closing of the bridge at night is not an acceptable way to treat a piece of public active transportation infrastructure. I’m prepared to accept that we cannot have the Copenhagen-style transportation amenity I would prefer, but I am still hopeful we can find a compromise that provides an accessible, reliable, and attractive transportation connection. We are not there yet. (And please remember, I am only one member of a Council of seven, and I cannot speak for them).

To answer what seems to be your main concern, I don’t know when the Marine Carriers were first consulted on this project, but the Port (who provides the Marine Carriers their authority) were clearly involved from day 1. They preferred an upstream location (now prefer a downstream one) and created the 22m by 100m “window” that led to the original 22m-high bridge concept, and have now led to evaluation of several swing/bascule concepts. Clearly, the City and our engineers have been searching for a creative solution to make what the politicians and public want mesh with the rather strict requirements of those who regulate the river and transportation. But serving those two/three masters is why the City is taking this iterative, slow approach, and why “plans that keep changing” are a sign of progress, not failure.

One thing to think about is that every step of this process costs more than the previous step, and moving backwards costs most of all. As engineering analysis and design gets more detailed, it gets more expensive, so we don’t want to do the detailed work twice. We could have asked for a ready-to-build concept a decade ago, and done enough detailed design that we just needed to pull the trigger and we could have it built within a year, and then taken it to public consultation. But if things are found that don’t work (i.e. the initial 22m height), we have spent a lot on a concept we now need to spend more on to change. Instead, we do feasibility studies, take it to stakeholders, the public, the regulators, and are given feedback. We then develop the concept to get more engineering done, and again have a look at the result and either move forward or change track depending on feedback.

This is a responsible way to plan, design, and pay for a public amenity. It is an iterative process, because as a government, we need to do our best to meet the needs of residents, of taxpayers who are footing the bill, of the regulations at 4 levels of government that have a thousand ways to limit our excesses, and of people who may be impacted by every decision we make.

If a government claims to do three years of stakeholder and public engagement, detailed engineering analysis and business case development, then turn around and deliver to you the exact same proposal they managed to render in a 3D model three years ago when the analysis started, then you know their consultation was bunk.

And I guarantee you, for every person who complains “this project has changed since the public consultation”, there are two who will say “public consultation never changes anything, they are going to ram their idea through regardless of what we say”. Actually, the same person will often say both, completely unaware of the irony. And that is why I appreciate your honest comments Ken, it sounds to me like you are trying to understand, not just complaining. So please provide your comments to the Engineering department and to Mayor and Council, and you will be heard!