C D asks—

Just wondering if anything can be done to keep vehicles from running the red right turn light at Columbia Street and McBride. I walk this way everyday from Columbia Stn to Victoria Hill and it’s an enjoyable walk until I get there. Today a vehicle stopped only to be passed on the left by a vehicle that was behind the stopped vehicle. This is a daily occurrence just on my walk but I know this happens to other pedestrians and cyclists. Someone is going to be killed. Perhaps we can have a railway crossing arm that can come down?

I hate this crossing. I have railed about it in the past, and even wrote a blog post about it here back before I was elected and when I was little more sassy than I am now (there is a funny story in here about how an outgoing city councillor tried to use that blog post to scupper my first election campaign – but that’s a long digression). Even since then, there have been suggestions to fix the crossing and the signage and lighting has been changed to better address the confusion drivers seem to have. I do not think there will ever be a physical barrier installed in that spot and we (vulnerable road users) are just going to have to keep acting with an overabundance of caution until the entire thing is torn up and replaced along with the Pattullo Bridge replacement, which will be starting in the next year or so.

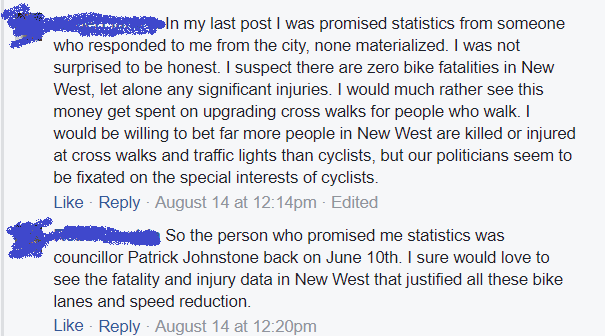

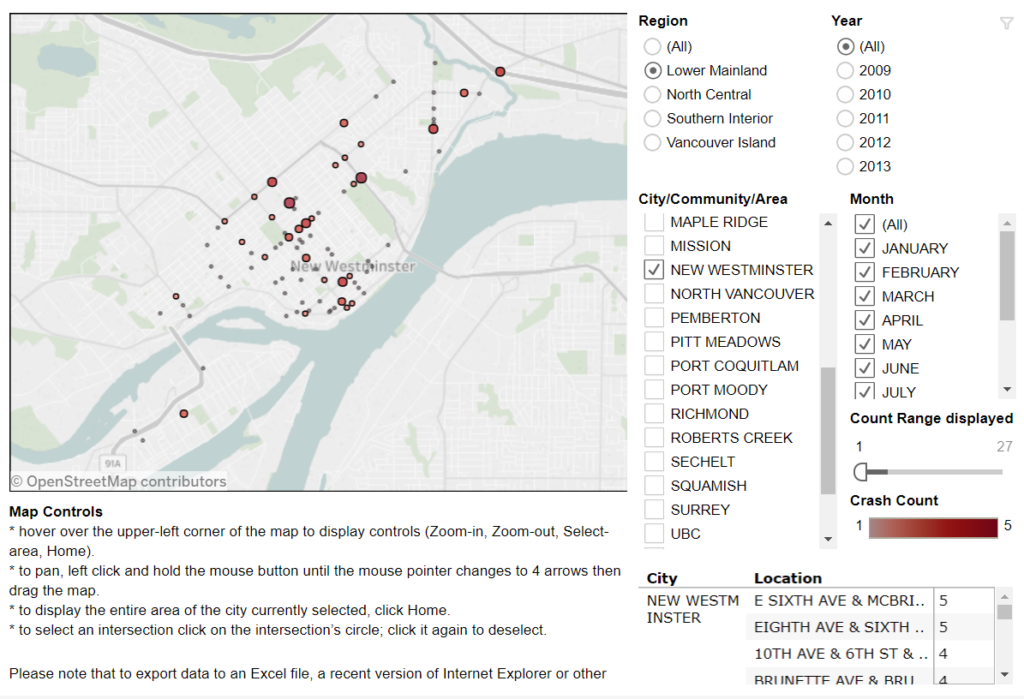

But why wait and not do something sooner? Because there is no obvious engineering solution that meets the current design code and is remotely affordable to do. People often suggest “what cost can you put on saving a life!?” when I say something like that, but I need to point out that this is one of more than a thousand intersections in the City, and by technical evaluation and statistical analysis it is not the most dangerous one for pedestrians by far. Those analyses are the way that staff decide which intersections to prioritize the (necessarily) limited budget of time and money into pedestrian improvements.

For example, the unmarked pedestrian crossing at 11th Street and Royal Avenue is current Pedestrian Enemy #1, so that block of Royal is currently being reconfigured to make it safer. There are a few other priority crossings, and staff are constantly updating the priority list and figuring out what interventions provide the best cost/benefit ratio. I’m not a transportation engineer, so I have to rely on their analysis when it comes to determining relative risk and how to prioritize to most effectively reduce pedestrian risk. Either that, or rely on anecdotal feelings about different intersections, but I think the former serves the community better.

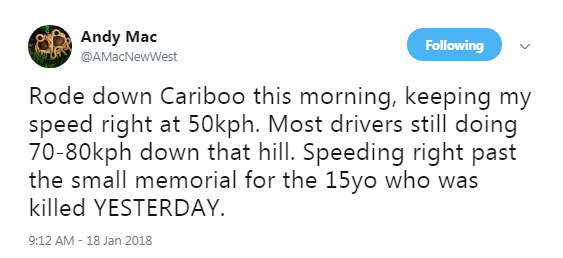

I hate to say it, but “someone is going to get killed” is not a characteristic that separates McBride and Columbia from most urban intersections. Although New Westminster has been fortunate in the last couple of years and have not suffered a pedestrian fatality, the reality is that the ongoing trend towards improved driver and passenger safety is not reflected in the pedestrian realm. In Morissettian Irony, it is getting more dangerous to be a pedestrian around “safer” cars. There are several alleged reasons for this, but the most likely one being the increased size, mass, and power of vehicles with which vulnerable road users are meant to share the road. The only logical response to that is slower speed limits (working on it) and better design of intersections. But with 1,000+ intersections in a little City like New West, and many that need expensive interventions, that is not a quick fix.

I am more convinced every day that the real fix is more than engineering, though. This intersection is one where there is signage, lighting, a painted crosswalk, and yet some significant percentage of drivers just don’t follow the rules. Are they unaware, inattentive, or do they just not care? Likely, there is a Venn diagram where these three factors overlap, and no amount of engineering can fix all of these.

This has me more frustrated every day, and more wondering how we are going to get the real culture change we need to make our pedestrian spaces safe. We need to change the culture of drivers, of law enforcement, and of the entire community to address the fact people in cars are killing people who are not in cars, and that threat is making our cities less livable. We need to educate people about the actual risk they are posing to others every time they step into a car. And we need more active enforcement of the specific traffic laws that serve to protect vulnerable road users, because you apparently cannot engineer negligence and stupidity out of road users.

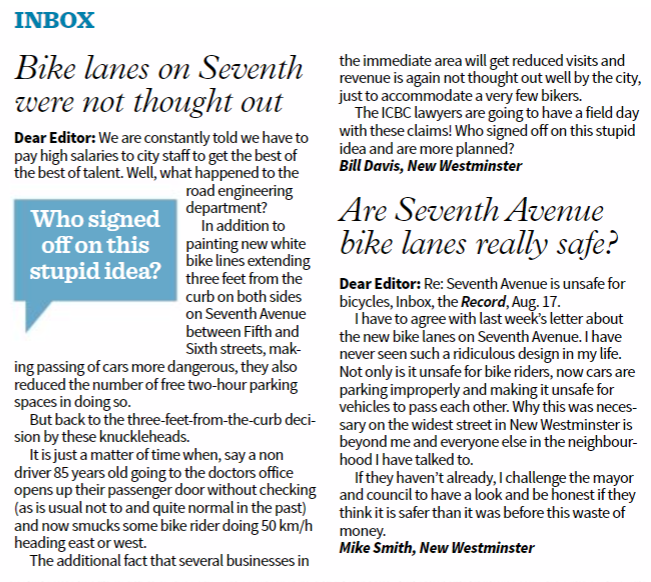

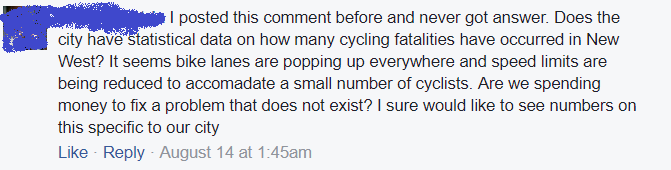

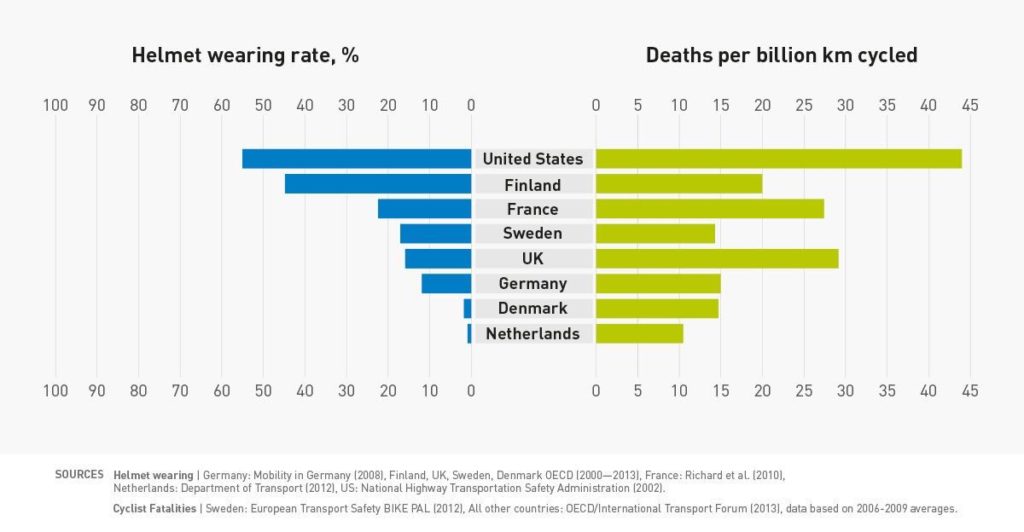

And worse, every time a City tries to build engineering to protect vulnerable road users, such as better crossings, longer cross signals, separated cycling infrastructure or curb bump-outs, we are bombarded by entitled drivers whinging about how pedestrians and cyclists don’t follow the rules (just read the comments). This despite clear evidence that the vast majority of pedestrian deaths are a result of the *driver* breaking the rules. This is a cultural problem rooted in entitlement, and I don’t know how to fix it.

To be clear: we need to acknowledge that the automobile is the single most dangerous technology we use in our everyday life, and stop being so blasé about the real risk and damage it causes. We also need to stop telling ourselves lies like automated electric cars are going to make life better – they demonstrably are not. But that is another entire blog post.

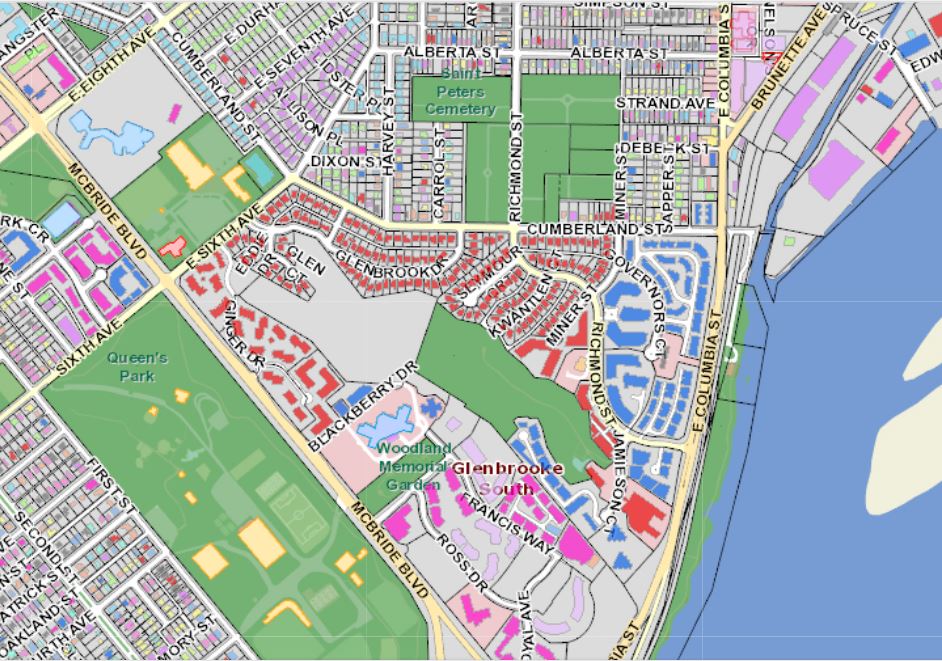

But that is just a representative cross section. There is another issue that makes the pedestrian experience even more uncomfortable. If you look at the intersection of Richmond and Miner, where staff were asked to evaluate placing a crosswalk, you see the corners are rounded off to facilitate higher turning speeds:

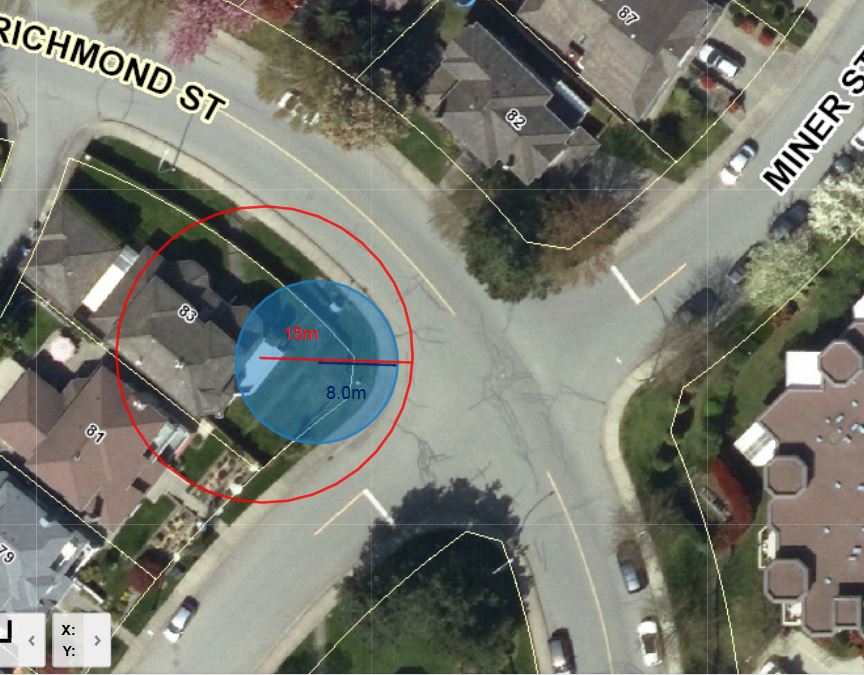

But that is just a representative cross section. There is another issue that makes the pedestrian experience even more uncomfortable. If you look at the intersection of Richmond and Miner, where staff were asked to evaluate placing a crosswalk, you see the corners are rounded off to facilitate higher turning speeds: The technical term for this shape is “Corner Radius”. In this diagram you can see the curb follows a curve with a radius (blue) of about 8m, and the effective turning radius (tracing the track a vehicle would actually use for a right turn) is closer to 15m. By modern standards, this is a crazy wide corner, more suited for a race track than an urban area. Reading up on

The technical term for this shape is “Corner Radius”. In this diagram you can see the curb follows a curve with a radius (blue) of about 8m, and the effective turning radius (tracing the track a vehicle would actually use for a right turn) is closer to 15m. By modern standards, this is a crazy wide corner, more suited for a race track than an urban area. Reading up on

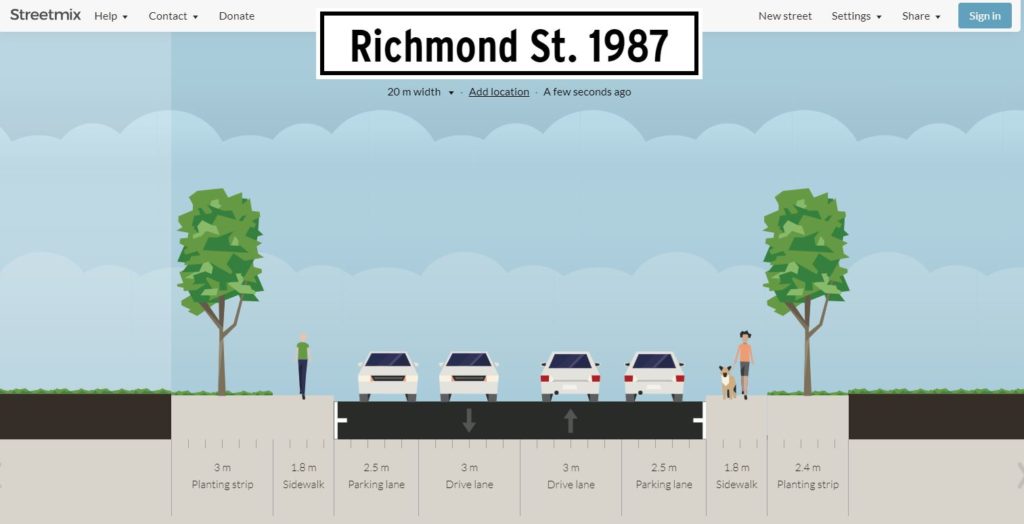

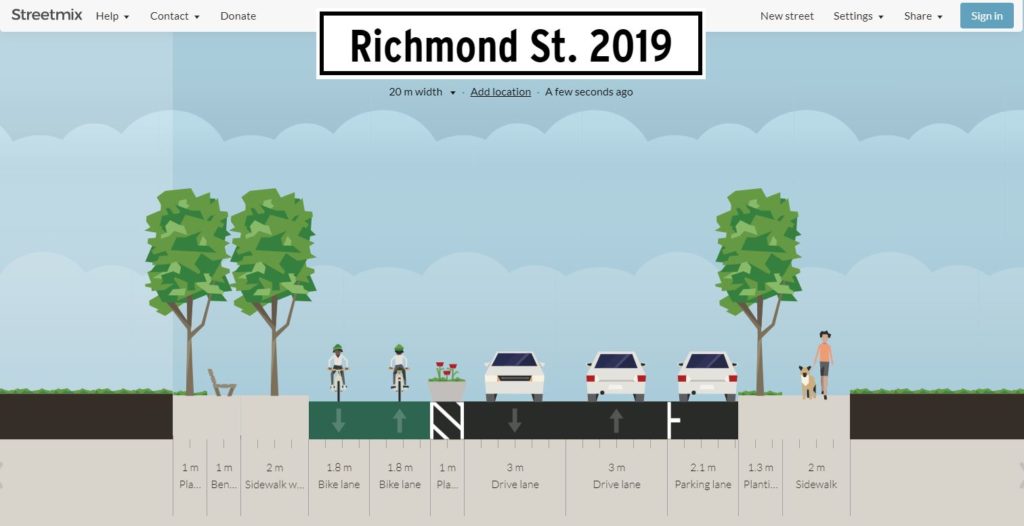

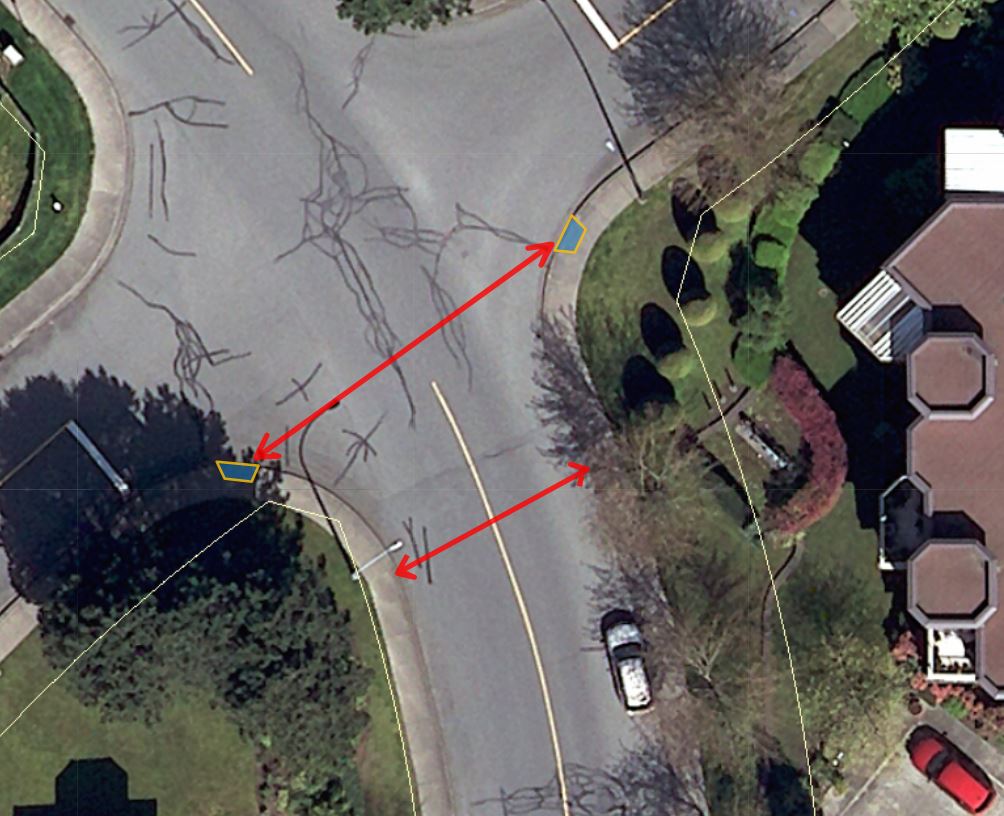

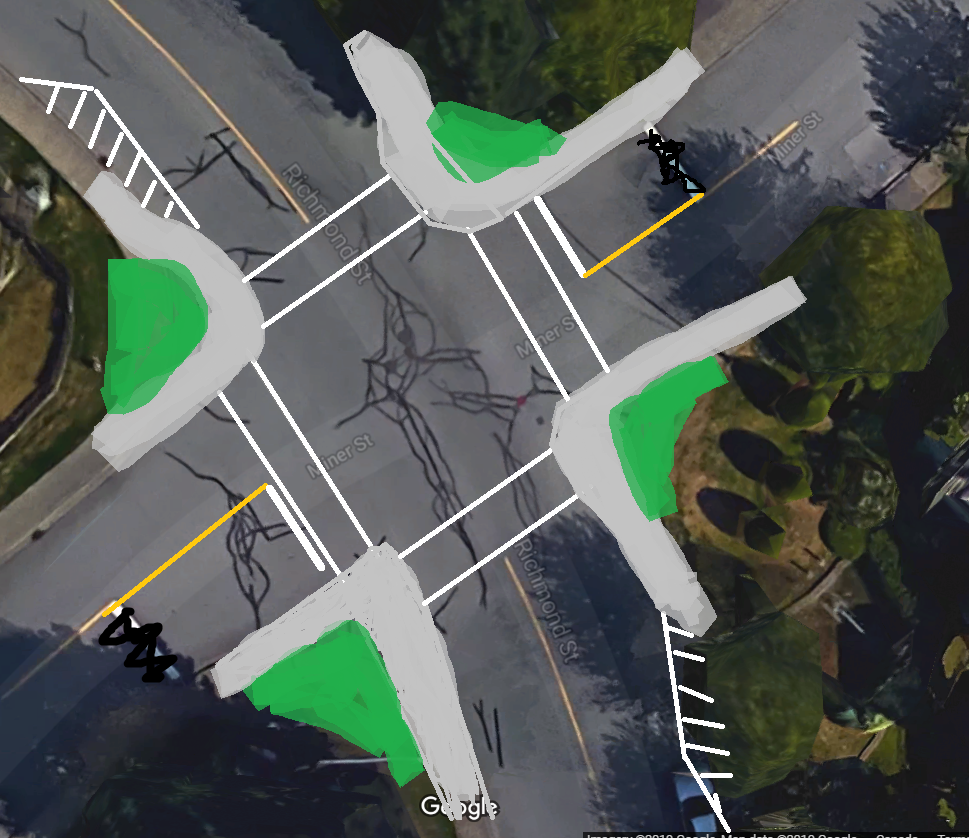

The Crosstown Greenway improvements are very small part of our transportation budget (less than 3% of this year’s budget for road improvements), and has numerous potential benefits to the community at large. As the City’s first foray into modern separated bikeway design, it may have a few kinks to work out, and it may take a bit of time for drivers to get their head around the new layout, but it is based on

The Crosstown Greenway improvements are very small part of our transportation budget (less than 3% of this year’s budget for road improvements), and has numerous potential benefits to the community at large. As the City’s first foray into modern separated bikeway design, it may have a few kinks to work out, and it may take a bit of time for drivers to get their head around the new layout, but it is based on