I took a vacation. After a busy but very rewarding year with too much work, a too-stuffed schedule, and too little recreation time, it was good to get away for a couple of weeks and chill.

Of course, I read some books about urban planning (reviews soon, if I get time) and spent a lot of time looking at the urban realm while tracing the career path of Peter Stuyvesant. Here are three thoughts.

1.City Bikes are cool.

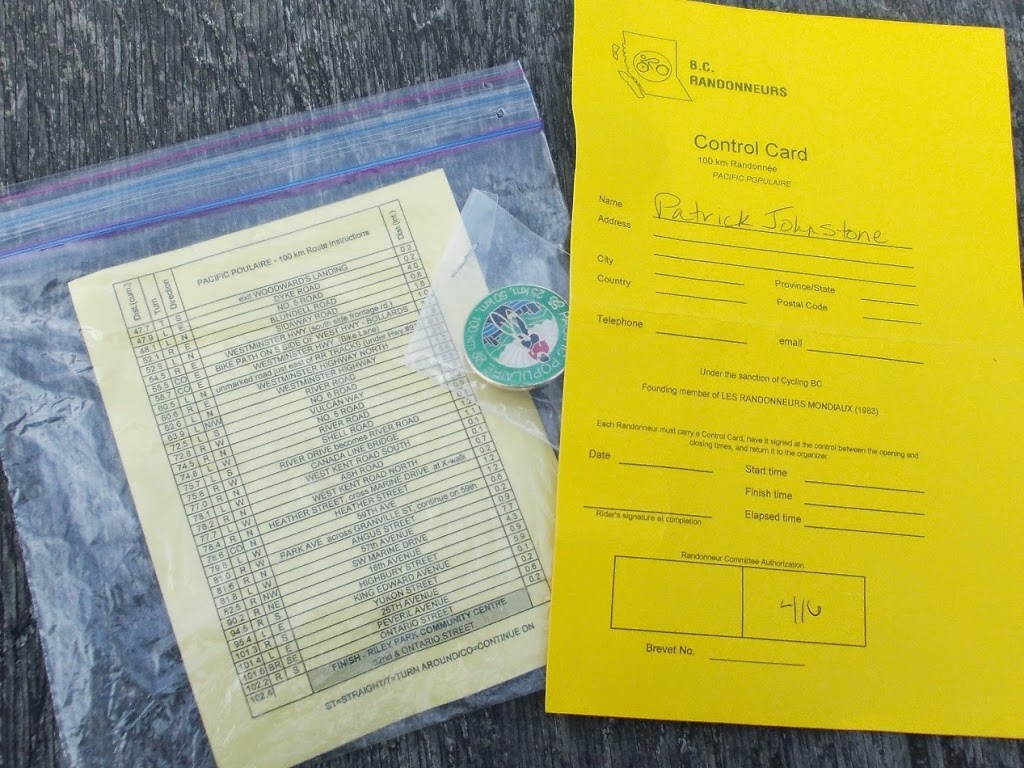

This is New York’s bike-sharing program, and while spending an unseasonably warm Christmas in Brooklyn, we had an opportunity to spin around on the almost-ubiquitous blue bikes.

The bikes themselves are sturdy Dutch-style upright bikes with full fenders, enclosed chains (no grease to worry about), simple but effective three-speed internal hubs, drum(!) brakes, and hub-generator powered lights. Tough? The bikes are (to paraphrase Neal Stephenson) “built as if the senseless dynamiting of [Citybikes] had been a serious problem at some time in the past”. They are pretty much a perfect balance between bulletproof and efficient.

There are many options to pay, from paying for a single ride to buying an annual pass. We bought a couple of 24-hour passes for $10 each. This gave us unlimited access for 30-minute rides. We were able to ride from our apartment in Bedford-Stuy to Barclay Centre, then from Braclay to downtown Brooklyn. Dropping bikes at a convenient station (you are never more than a 5-minute ride from a station within the service area), we walked across the Brooklyn Bridge, wandered around a bit in Manhattan, picked up a couple of bikes in Little Italy, rode across the Williamsburg Bridge, dropped bikes and visited a microbrewery, etc., etc.

Actually, bulletproof and efficient pretty accurately describes the entire system. The kiosks and payment process is simple to use, and features a little digital map you can scroll around to navigate your neighbourhood, the on-line app will guide you to the nearest station (if your 30 minutes are running out), and there are very few surprises.

Is the system successful? 10 Million individual rides in 2015, and ongoing expansion plans to reach 12,000 bikes and 700 stations by 2017. Before anyone talks to me about my helmetless pictures above (Hi Karon!), there is no helmet law in New York, and with literally tens of millions of rides since its inception 2013, there has never been a fatality or a serious injury on a City Bike. Looking at NYC’s pedestrian and traffic fatality stats, CityBike may be the safest way to travel in the Big Apple.

Yet, globally, no jurisdiction with a helmet law has successfully launched a bike-share program like Citybikes. Every one has failed, or failed to launch. And I predict Vancouver’s will fail for this very reason.

2. Even in New York, pedestrians are serfs.

Walking Fifth Avenue from Central Park to the Empire State Building is an incredible experience. From the Plaza, past the Library and Rockefeller Center and St. Patrick’s Cathedral, through the (unofficial) centre of world shopping, it is a spectacular combination of sights and sounds and people and shopping and urban buzz. A couple of days after Christmas, I got to share it with tens of thousands of other people.

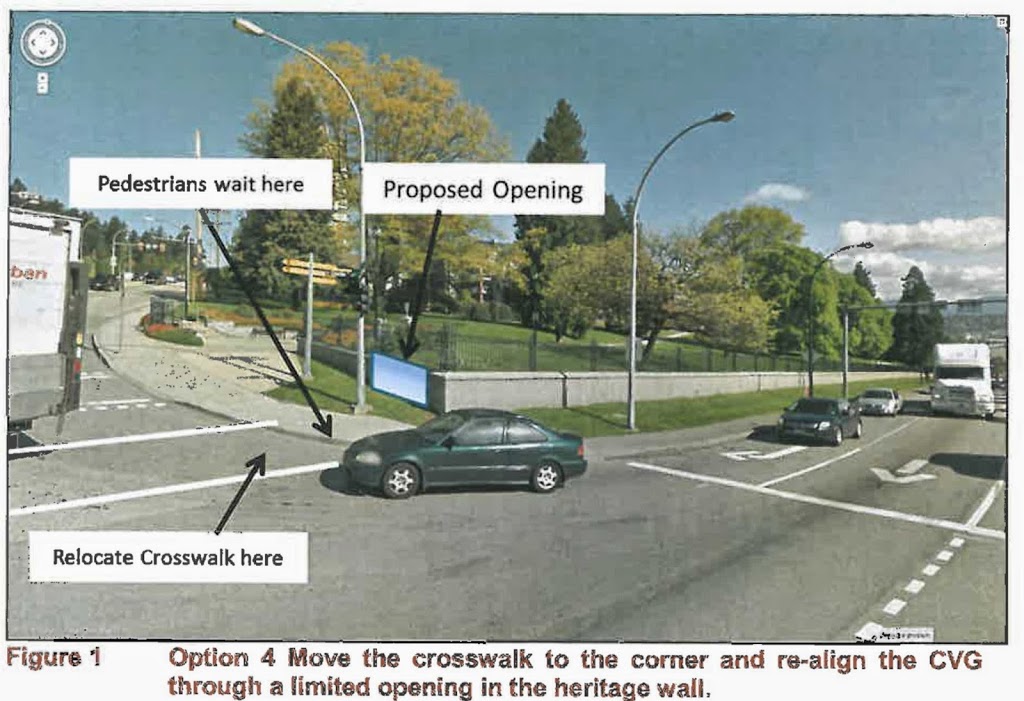

It got rather more intimate than most would probably like, because all of those people were crowded behind barriers on too-narrow sidewalks as hundreds of police spent their holidays keeping the vast expanses of asphalt between the sidewalks free for the movement of – a couple of dozen cabs and towncars.

Just look at this photo and look at how the public realm is divided up. 4m sidewalks, 20m of road, and look at where the people are. Overall, New York City is one of the most walkable places on earth, and between the incredibly convenient subway system (although, I noted only about 10% of station were accessible for people with disabilities!), short distances to get any kind of shopping you might want, and a huge reliance on walking as the primary form of transportation – the guy in the town car somehow gets priority to an opulent amount of the public space. It’s bizarre.

3. Aruba may be the Netherlands, but it ain’t Dutch.

We picked Aruba for our vacation because we didn’t want adventure this year, we just wanted to chill on a beach, and according to legend, Aruba’s beaches are amongst the best. A legend I will whole-heartedly confirm.

However, we were also intrigued by Aruba’s Dutch heritage (it is still part of the Kingdom of the Netherlands), and hoped to see a little of the Dutch personality of the island. Unfortunately, aside from ubiquitous Heineken and plenty of young Dutch nationals working the tourist bars and restaurants, there was not a lot of Amsterdam to be found in Aruba. For a small island with incredibly pleasant weather, It was a depressingly car-oriented community. We used the local bus service (inexpensive, predictable, convenient, almost empty) and walked most of the time, where most people used cars, truck, atvs, and motorcycles. The only cyclists we saw were of the lycra-clad sporting type. The pedestrian realm ranged from non-existent up on Malmok where we were staying to downright hostile once you got a block off of the tourist strip in the resort areas.

Maybe we should try Curacao

4. Vacation notwithstanding, it’s good to be home.

And I am realizing that New Westminster has pretty much all of the assets that Jane Jacobs mentions when talking about vibrant communities, which is a hopeful sign…