We had a report at the September 28th Council meeting that I mentioned in my blog, but skipped past the details of, because I think it was too important a report to bury in a long boring Council Report. This is the Corporate Energy and Emissions Reduction Strategy (CEERS).

The City has two roles in addressing greenhouse gas emissions and meeting the Paris Agreement goals that the City, the province, and the nation have all stated they intend to meet. One is making it possible for our community (residents, businesses, industry) to meet the goals, which is addressed through a Community Energy and Emissions Plan (“CEEP”). The second is managing our own corporate emissions, those created by the City in operating its own buildings and fleet. The CEERS is our updated plan to deal with this second part.

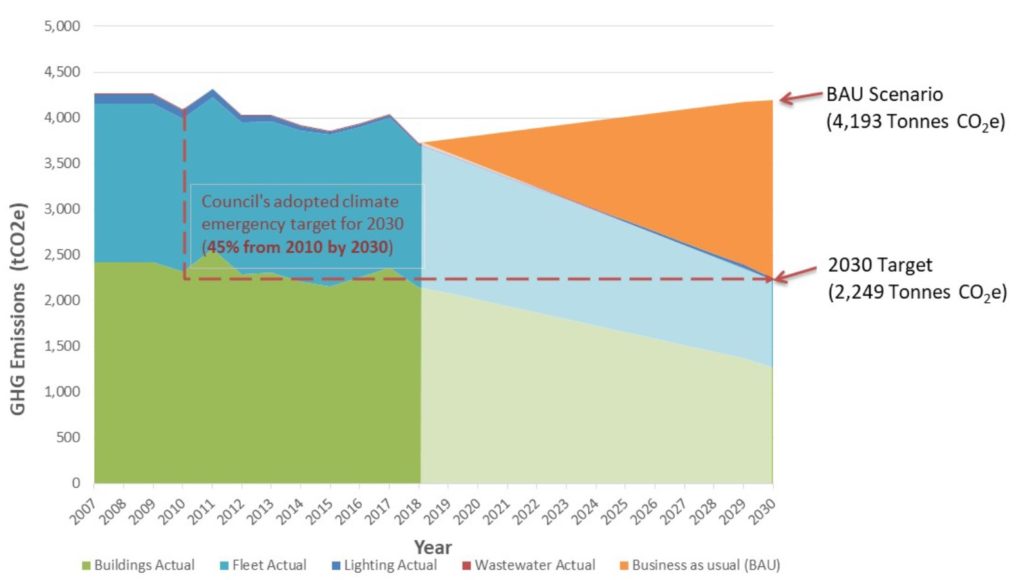

This CEERS replaces an older plan that was adopted in 2008 and reduced our emission by 12% over the last decade. CEERS 2020 outlines the strategy to get us to our newly stated and ambitious goals – reduce emissions to 45% below our 2010 baseline by 2030 as the first step towards a 100% reduction by 2050. I think the most important part of any climate policy is that we set goals within a viewable horizon – ones we need to take action on *now* to achieve, because as bold as 100% by 2050 is, the 30 year timeframe gives too much cover to those willing to kick climate action down the road.

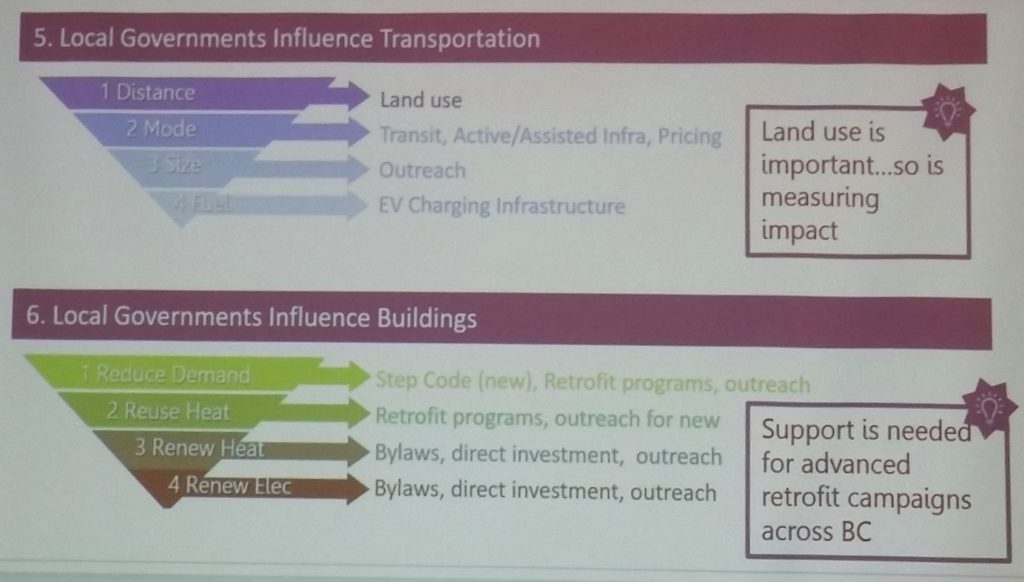

This Strategy lays out a clear path to get our building and fleet emissions to our 2030 goal. Replacing the Canada Games Pool with a zero-carbon building will be a huge step, but there are 13 other buildings in the City that would see energy and emissions reduction measures soon. This would reduce our building emissions by 55%, and would pay us back in energy savings within 10 years. We are also going to be taking a much more aggressive approach to electrification of our vehicle fleet to reduce those emissions by 30%, both by buying electric vehicles, and by updating our infrastructure to provide charging to these vehicles. With these two strategies and continued improvement on smaller-emission sources like street lighting and wastewater, we can get to our 45% goal by 2030.

That doesn’t mean we will be done in 2030. We will then have harder work to do to find a path to carbon-neutrality that we are aspiring towards in our Bold Step #1. Things like deep retrofits of some other buildings in the City, exploring alternate energy sources (renewable gas, hydrogen, solar, etc.) and creating an offset program through reforestation or other strategies. We can also anticipate that technology will catch up to our goals in the decade ahead, making the next steps a little easier. For example, it is simply not viable to have all-electric or hydrogen fuel cell fire truck fleet today, but we will be relying on those types of changes to emerge after 2030 when those deeper reductions are needed. So if we are going beyond just picking low-hanging fruit now, we are still harvesting the riper fruit.

There is a lot of great policy in here aside from just purchasing changes. We are going to start internally pricing carbon at $150/Tonne. This means we will account for our internal emissions, and use that value to inform our purchasing programs for new equipment. This value (about $650,000/yr based on 2020 emissions) will go into a Climate Reserve Fund to help pay for carbon reduction projects. This both provides internal incentive for departments to find lower-emission approaches (as the cost comes out of your departments budget) and provides us a clear fund and budget line item to apply to emergent projects.

Overall, the cost of implementing this plan is about $13.5M, though much of it is already included in our 5-year capital plan. To put that number into context, we annually spend about $700,000 on fossil fuels (gasoline, diesel, propane) for our current fleet, and energy to heat and service our two dozen buildings (pools, rec centres, City Hall, etc.) is about $1.2 Million per year. It doesn’t take complicated math to recognize that reductions in these costs will rapidly offset the capital costs invested today. With interest rates as low as they are, and senior governments telegraphing their intent to support this type of green infrastructure renewal with grants, the time is now. The City Council of 2030 will be saving a lot of money because of the commitment we make today.

We are going to get there. We can get there. To delay any further would be irresponsible.